Our History

The St. George’s Society of Baltimore traces its origin to the very last day of the Year of Our Lord 1866, when a group of English gentlemen gathered in Baltimore to organize “The St. George’s Society.” Their purpose was “to afford relief and advice to indigent natives of England or Wales and the British Colonies, or to their wives, widows, or children; and to promote social intercourse amongst its members.”

The meeting had been convened by British Vice Consul Mr. Stewart Darrell, presumably at the request of Mr. George H. Williams, described by the first secretary, Mr. James Belden, as “the father of the Society.” From its inception, the organization blended compassion with camaraderie, a union of charitable duty and English fellowship that continues to define the Society today.

Founding and Early Growth

In February 1867, the Maryland Legislature formally incorporated the Society. At its inaugural meeting, officers were elected and a constitution adopted establishing the name “The St. George’s Society of Baltimore.” The charter declared that ten members would form a quorum for elections and that a permanent charitable fund should be maintained in trust by the president and treasurer, an early sign of prudence and purpose.

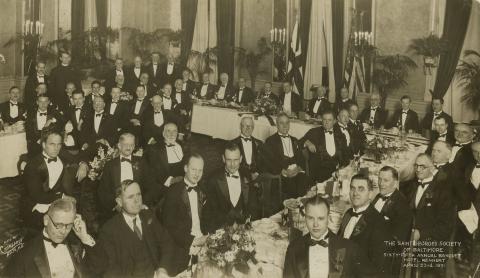

That same year, members began the annual tradition of celebrating St. George’s Day on April 23 with a formal banquet, a custom that continues today. Early meetings and dinners were held at prominent Baltimore establishments such as Guy’s Monument House and the Rennert Hotel, later moving to Barnum’s Hotel at Calvert and Fayette Streets, where members gathered to dine, toast, and uphold the fellowship of Englishmen abroad.

The Society’s first official record, presented in the Secretary’s Annual Report of 1868, reveals the deeply personal origin of its mission:

“The two orphan children, C___ and H___ F___ R___, who were the immediate incentive to the formation of this Society, and who were 8 and 9 years of age [when] placed in asylums even before the Society was formed, are well and happy. They are occasionally visited and cared for by one or more members.”

A later report in 1872 identified their late father, C___ R___, as a chemist and noted that his son had been placed at the Manual Labor School after leaving the Stricker Street Orphan Asylum, while his sister entered the Christ Church Orphan Asylum. Though the children’s later lives are unknown, their plight inspired a fellowship that has endured for more than 150 years, an organization devoted to the welfare of others.

The Society’s first chaplain, Reverend Dr. Milo Mahan, helped shape its moral and civic character. A scholar and theologian of uncommon intellect, Mahan was also the brother of Professor Dennis Hart Mahan, a revered instructor of military engineering at West Point. Dennis’s son, Alfred Thayer Mahan, was expected to follow his father’s path into the Army, but under the persuasive guidance of his uncle, Reverend Mahan, he instead entered the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis.

That decision would alter the course of history: Admiral Mahan’s seminal work, The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1890), transformed naval strategy, inspired the expansion of maritime powers such as Britain, Germany, and Japan, and shaped global affairs well into the twentieth century. The Society’s first chaplain thus stands not only as a moral founder of this organization but also as an indirect catalyst of ideas that changed the modern world.

Resilience and Benevolence

Through hardships such as the Panic of 1873, the Society raised funds to aid destitute Britons in Baltimore and to maintain its charitable fund. Quarterly meetings and annual banquets preserved English social customs while nurturing generosity and friendship. A Relief Committee, formed in 1894, strengthened the Society’s charitable oversight, a system that still guides its work today.

Victorian and Edwardian Eras

The Society celebrated Queen Victoria’s Jubilees with enthusiasm and sent £500 to the Transvaal War Fund during the Boer War. In 1900, it hosted a young Winston Churchill, fresh from the front lines, for a lecture in Baltimore. Among the distinguished members attending was Dr. William Osler, the renowned physician and professor at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler, one of the four founding professors of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, revolutionized modern medical education by establishing bedside instruction and postgraduate residency training. His membership in the St. George’s Society connected Baltimore’s British expatriate community to one of the most celebrated medical minds of the age, a man later appointed Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, the most prestigious medical chair in the English-speaking world.

Following Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, the Society erected a granite obelisk in Druid Ridge Cemetery, believed to be the only monument to the Queen in the United States. Each May 24, members laid a wreath there for over a century.

That same year, the Society adopted its seal and badge, bearing the red cross of St. George and the motto “True to Our Trust.” Tragically, the original die for the badge, along with many early records, were lost in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. In later years, new versions were created from memory, and in 2021 the design was faithfully re-created by Toye, Kenning and Spencer for today's members.

In the years immediately following, the Society found itself navigating questions of identity as Britain entered the new Edwardian age. During this period, spirited debate arose over the long-standing order of toasts at Society banquets, whether to honor the U.S. President or the British Monarch first. The discussion reflected both Baltimore’s deep American patriotism and the Society’s enduring pride in its British heritage, emblematic of its proud yet complex Anglo-American character.

The Titanic and the Great War

The tragedy of the RMS Titanic in April 1912 deeply moved the Society. The annual banquet was canceled in mourning, and the funds reserved for the celebration, along with additional member donations, were forwarded to the Titanic Relief Fund in London to aid the families of the lost. That same year, the Society provided support to British families affected by the loss of the Baltimore-based steamship Julia Luckenbach.

Two years later, the outbreak of the First World War profoundly expanded the Society’s charitable reach. Members transformed their mission from local aid to trans-Atlantic relief. They organized emergency lodging for British sailors stranded in Baltimore, served more than 1,100 meals to visiting servicemen, and raised funds to send destitute countrymen home. The Society also contributed to the Prince of Wales Fund and other wartime charities in Great Britain.

At the same time, its members gathered supplies, collected clothing and blankets for Red Cross shipments, and provided moral and financial support to British families living in the city. The Society’s records note that over 100 Englishmen were assisted with transport arrangements back to the United Kingdom during the conflict.

The war also brought loss close to home. Among the losses felt most keenly by the Society was that of Mr. Montagu Grant, a beloved member, who at one time, had arranged a visit of the British cruiser squadron to Annapolis. He perished with his wife when the Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat in 1915. Though residing in Chicago at the time of their deaths, the Grants had lived in Baltimore for fifteen years and remained active in the Society, returning often to visit friends and former colleagues. Mr. Grant, a devoted Briton and employee of the American Can Company, was remembered for his loyalty and friendship. Their loss was deeply mourned within the Baltimore English community and remembered at a special meeting of the Society later that year.

By 1917, wartime demands had exhausted the Society’s treasury, forcing it to sell its furnishings and close its clubhouse until peace returned, but the members’ dedication to relief work never wavered.

World War II and Continued Service

When war again engulfed Europe in 1939, the Society promptly offered assistance to Lord Lothian, the British Ambassador to the United States, and established a War Committee to coordinate charitable and relief work. In partnership with the St. Andrew’s Society and the St. David’s Society, it arranged a clubroom at the Southern Hotel in Baltimore for officers of the British Merchant Navy whose ships were in port. There, visiting sailors could find companionship, mail, news from home, and a comforting sense of kinship far from Britain’s shores.

The Society raised substantial funds for British War Relief, contributing to the purchase of a mobile canteen in Great Britain, and provided direct assistance to British subjects stranded or in need in Maryland. It organized clothing drives, collected Red Cross supplies, and helped locate burial plots for British servicemen who died while serving abroad. Throughout the war years, it also collaborated with the British Consulate to arrange memorial services for those lost at sea and to ensure that widows and dependents of merchant sailors received proper care.

By the war’s end, the Society had assisted more than 300 British citizens in returning home, funded 18 wartime burials, and sustained the morale of the countless sailors who passed through Baltimore’s harbor en route to the Atlantic convoys. Its work embodied the Society’s motto, “True to Our Trust,” and reaffirmed its reputation as a steadfast ally of Britain in times of need.

Postwar and Modern Era

Following the Second World War, the Society continued its mission of fellowship and charitable service. It provided aid to British war brides, merchant seamen, and local families in need, while maintaining its hallmark observances, the annual St. George’s Day banquet and Empire Day celebration. Distinguished guests continued to include Commonwealth ambassadors, military officers, and civic leaders, reinforcing the Society’s dual heritage as both proudly British and resolutely Baltimorean.

Affiliation with the Royal Society of St. George (1961)

In 1961, the Society marked two significant milestones in its transatlantic heritage.

On St. George’s Day, 23 April 1961, the Society presented a facsimile of the Lindisfarne Gospels to the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore. This illuminated manuscript, created around 715 A.D. on Lindisfarne Island in Northumbria, is among the most revered works of early English Christianity, uniting Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art in a single masterpiece. By gifting this facsimile, the Society shared a treasure of English spiritual and cultural history with the American public, ensuring that Baltimoreans could experience one of England’s most celebrated artifacts of faith and artistry.

That same year, on 19 May 1961, the Society became formally affiliated with the Royal Society of St. George, headquartered in London. A letter later received in 1969 acknowledged Baltimore’s long-standing place among the historic St. George’s Societies of America, Charleston (1733), New York (1770), Philadelphia (1772), and Baltimore (1867), each preserving the shared traditions of fellowship and service that have linked English societies on both sides of the Atlantic for nearly three centuries.

The 100th Anniversary and Royal Navy Visit (1966)

In 1966, the St. George’s Society of Baltimore celebrated its 100th anniversary, marking a century of fellowship and service with its 100th Annual Dinner at the Maryland Club. The occasion was made especially memorable by the visit of three Royal Navy submarines, HMS Osiris, HMS Orpheus, and HMS Walrus, whose commanding officers were honored guests at the banquet held on 23 April 1966.

The following day, Sunday, 24 April, the Society hosted officers and crew for a St. George’s Festival Service at Old St. Paul’s Church. Lieutenant Commander A. David C. Lund, Royal Navy, commanding officer of HMS Osiris, served as senior officer in overall command of the visiting submarines.

After the service, members and guests gathered for a coffee hour at the Peabody Museum, where the Governor of Maryland joined the Society’s President in cutting a commemorative cake honoring the Royal Navy visitors, a gesture symbolizing the enduring bond between Maryland and Great Britain.

Civic Leadership and Preservation

At a Board of Governors meeting on 27 July 1967, the Society received an application for membership from a man destined to become one of Maryland’s most influential public figures, William Donald Schaefer. His application was approved that October. Schaefer would go on to serve as Mayor of Baltimore (1971–1987), Governor of Maryland (1987–1995), and Comptroller of Maryland (1998–2006). His long and transformative public career, marked by the revival of the Inner Harbor and modernization of Maryland’s government, reflected the civic leadership and dedication to community that the Society has long valued.

The Society also counted among its members United States Senator George L. Radcliffe, a lifelong Marylander and public servant whose presence reflected the organization’s growing stature within the civic life of the state.

The St. George’s Society Foundation

During this same period, the Society sought to ensure the permanence of its charitable mission. On 9 February 1970, a resolution was introduced to establish a special fund for relief and burials, clarifying the administration of charitable disbursements. After legal review and deliberation, the proposal was formally adopted by the Board of Governors on 28 July 1971, laying the groundwork for what would become the St. George’s Society Foundation, a dedicated entity to steward the Society’s philanthropic purpose into the future.

Through these developments, the Society demonstrated that its mission, first articulated in 1866, remained alive and adaptable: to offer relief, preserve fellowship, and serve Baltimore and its British community with honor and integrity.

An Enduring Legacy

Today, the St. George’s Society of Baltimore stands among the city’s oldest continuous charitable and social organizations. Born of compassion for two orphaned children, tested through depression and war, and sustained by generations of fellowship, it continues to honor its founding charge: to provide relief to those in need and to promote goodwill among friends united by heritage and service.

References:

Sagerholm, Vice Admiral James. History of The Saint George's Society of Baltimore. 2013